The Republic of San Marino is not exactly on the list of the world's top

ten tourist attractions. No 747s land there, primarily because the

construction of a suitable facility would necessitate the razing of a

sizable percentage of the entire country. Even Piper Cubs have difficulty

landing on a mountain and, for all intents and purposes, that's all San

Marino is: a mountain.

In an age of superpowers San Marino could be considered a good-natured

joke, a Tom Thumb country (60 square kilometers with a population of

17,000) where postage stamps and souvenirs form the basis of the economy

and motor bikes and cars roar past a backdrop of castles, suggesting a kind

of Disneyland-in-exile.

However, San Marino offers many points of interest for the serous political

scientist and historian, as well as for the casual collector of

geographical oddities. For one thing, San Marino is the smallest and oldest

republic in the world. Situated in the heart of Italy, on Mount Titano near

the famous Italian coast resort of Rimini, the founding of this state is

credited to a Dalmatian stonecutter named Marino, in 300 A.D. A

Christian convert, Marino fled Rimini to avoid persecution from the Emperor

Diocletian. History relates that he settled down on the slopes of Mount

Titano as a hermit, content to lead a life devoted to the contemplation of

his faith and exercise of his art. However, other Christians followed,

accepting Marino as their spiritual leader and forming a community.

The story of Marino may or may not be apocryphal, but written records show

that by 85 A.D. San Marino was already a sovereign state, an established

republic with laws and a stable government. For the most part, that same

system prevails today, with some modifications brought about because of the

press of modern times.

But, with fewer inhabitants than ride a New York subway on a holiday, is

San Marino a nation? The answer is yes, at least by any reasonable criteria

that we may apply. First, San Marino is recognized as such by most other

nations of the world. Most important, its autonomy is recognized by Italy

which carries San Marino in the womb of its eastern coast. The republic

issues its own passports, and has a United States immigration quota of 150,

separate from the Italian quotas (Detroit has a large number of San

Marinese immigrants working in its automobile industry). Not to be ignored

in the diplomatic field, San Marino has signed treaties with various other

nations, including the United States, France, Great Britain and, of course,

Italy. They even have their own currency, although lire is the most

commonly used medium of exchange.

Any nation, however small, that has managed to endure for 16½

centuries must be considered a viable entity. San Marino is.

The republic has nine major population centers, but the most important of

these is the capital of the same name. This city of 1700 holds the key to

the riddle of how San Marino has been able to survive amidst the

complexities of the 20th century with all of its economic and geopolitical

rivalries. While more than half the population is engaged in agriculture,

and there are small industries, tourism is the pillar on which the economy

of the nation rests and is the major element in the life of each San

Marinese.

The key to San Marino's survival is the pervading medieval atmosphere of

the capital, an atmosphere the residents nurture and protect with shrewd,

pecuniary tenacity. The streets are lined with souvenir stands offering

plastic helmets, swords, and shields. For eight months of the year husbands

and wives peddle their wares, saving enough money to bide them through the

winter months when the mountain is quiet and shrouded in snow.

Other somewhat unique items available in the shops are 3 liter bottles of

cognac that sell for $2, ceramics from the nearby factories, and pastries.

For the most part, quantity is much more in evidence than quality. However,

San Marinese stamps are highly prized by philatelists, both amateur and

professional. All of the stamps (which are already carefully affixed to

every post card on sale in the country) are conceived, designed, and

executed by the government.

The ubiquitous souvenir stands and aggressive selling techniques often

leave San Marino open to charges of vulgar commercialism, of transforming

the winding, ancient cobbie-stone streets of their capital into the

equivalent of a Coney Island boardwalk. Two factors soften and mitigate

this charge: The nation needs this trade in order to survive (San Marinese

stamps and souvenirs are the equivalent of Iranian oil) and the poor

quality of the trinkets merely reflects a knowledge of the tastes of San

Marino's best customer—the tourist; as far as medieval memorabilia is

concerned, San Marino possesses plentiful amounts of the genuine article.

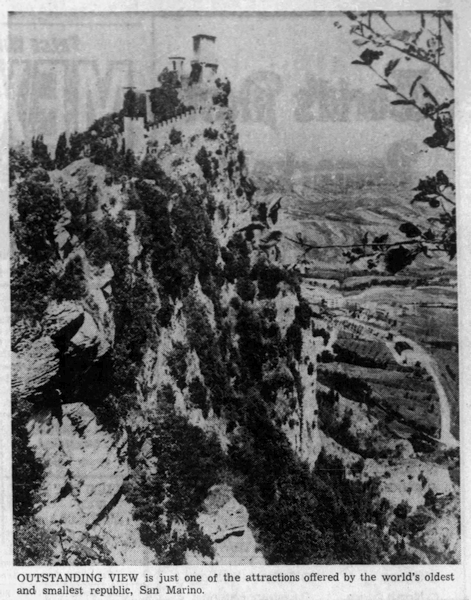

For example, the three castles that dominate the skyline, stamping their

collective personality on the mountain like stone ghosts from the distant

past. They are not mock-ups, but real; men bled and died defending their

ramparts. And they are in perfect condition, thanks in large part to

free-spending movie companies in the 1940's (Prince of Foxes, with

Tyrone Power, was filmed here).

The castles are fortresses, constructed over a span of four centuries. One

—La Cesta, or "2d Tower"—contains the Medieval Man's

complete armory, an extensive collection of arms and equipment from the

Middle Ages. Of course San Marino is, in many ways, a museum in itself. And

the citizens have taken great pains to keep it that way, eschewing most of

what we call "modern conveniences." You will find no urban

renewal projects in San Marino (of course, there are no slums), no

skyscrapers or modern office buildings. The memory of ancient times, etched

in the stones, is the meal ticket of the San Marinese, and they know it.

How seriously do the San Marinese take their own country? Very seriously.

They leave, but they also return, drawn back to the strange peace that lies

over the land like a comforting, invisible fog, a peace that appears to

arise from being "stuck" in time, an easy way of life that is

made even more precious and is magnified by the caca-phony outside their

borders.